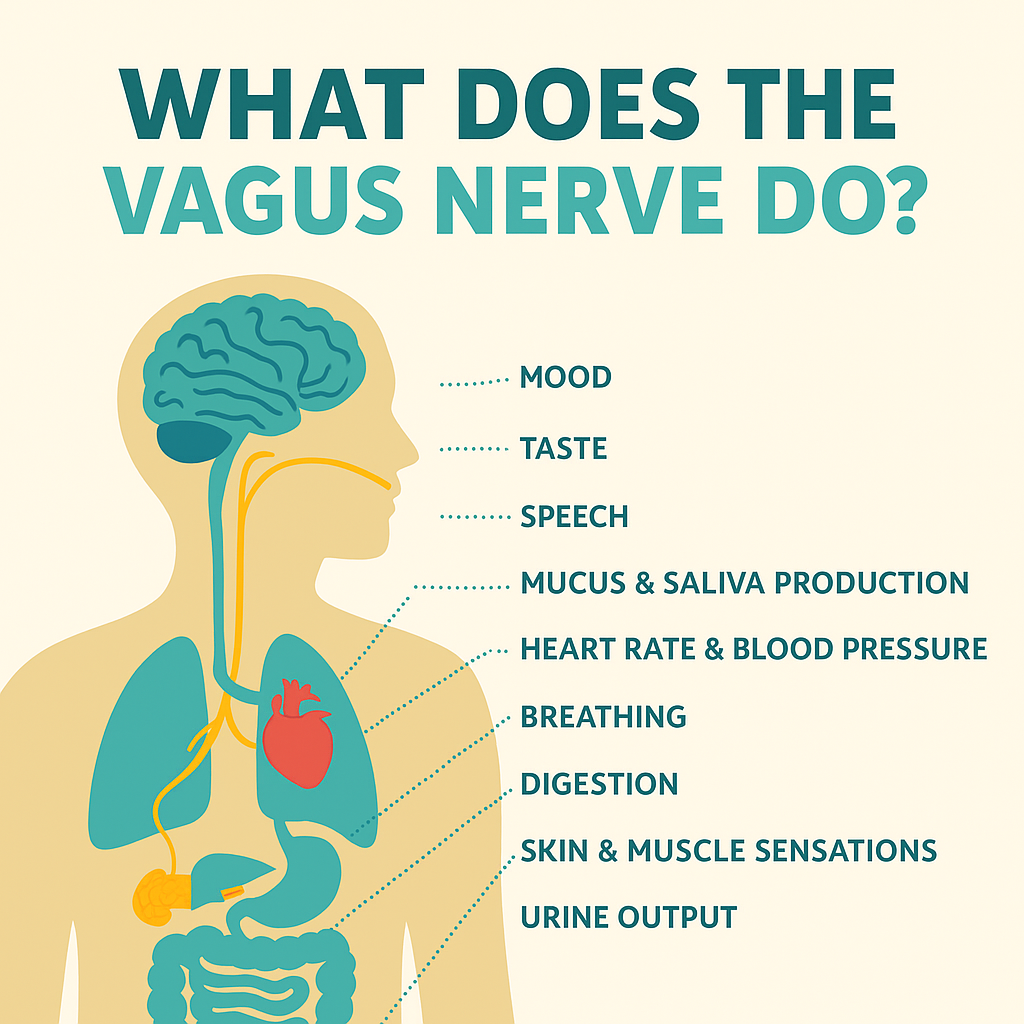

The vagus nerve (also known as the 10th cranial nerve) is one of the longest and most complex nerves in the body. It starts in the brainstem and then travels through the neck, chest and abdomen, branching to organs including the heart, lungs, digestive tract, liver, pancreas and more.

It is a major component of the autonomic (involuntary) nervous system and has a fundamental role in regulating heart rate, digestion, immune function, inflammation and, increasingly recognised the gut-brain connection.

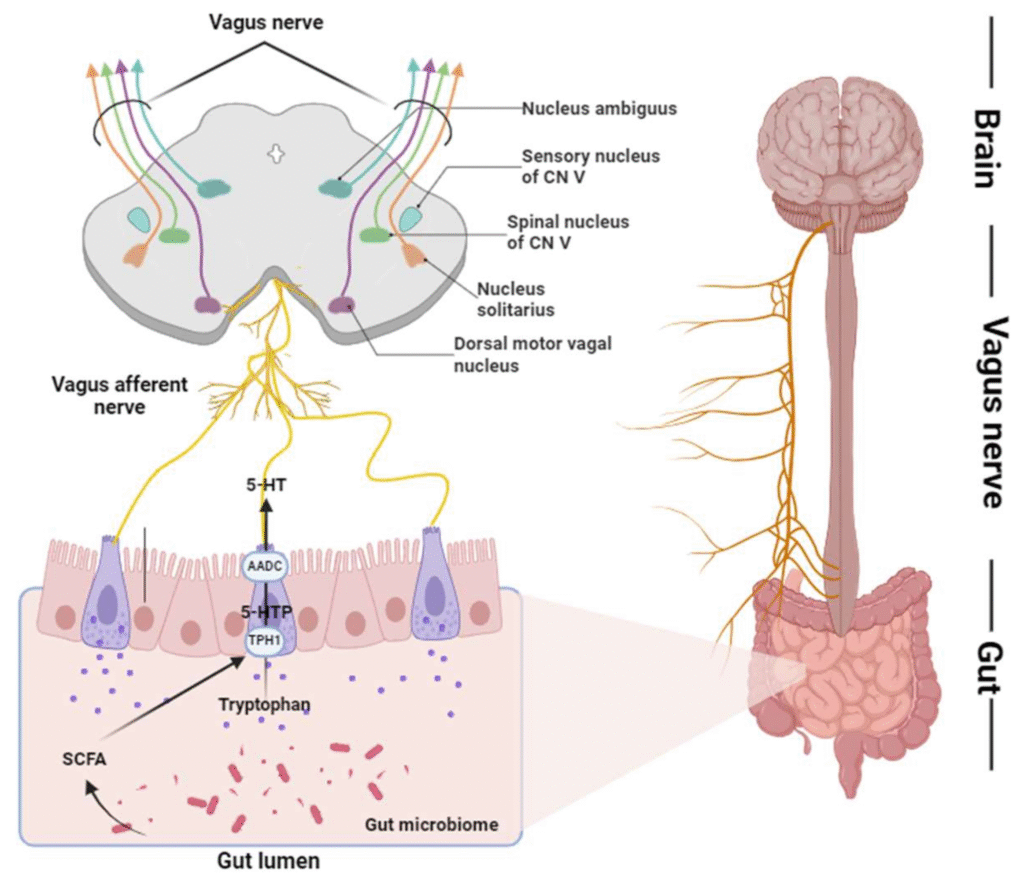

One of the most important roles of the vagus nerve is as a bidirectional communication channel between your gut and your brain. The “gut-brain axis” describes how the digestive system and the central nervous system talk to each other, and the vagus is a major highway in that system.

In effect, it helps coordinate what your gut is doing, how your brain responds (mood, cognition, stress) and vice versa.

So when the vagus nerve is functioning well, you have smoother digestion, better heart-rate variability (HRV), better stress resilience and a more regulated immune/inflammatory system. When it’s disrupted, many systems can go off-balance.

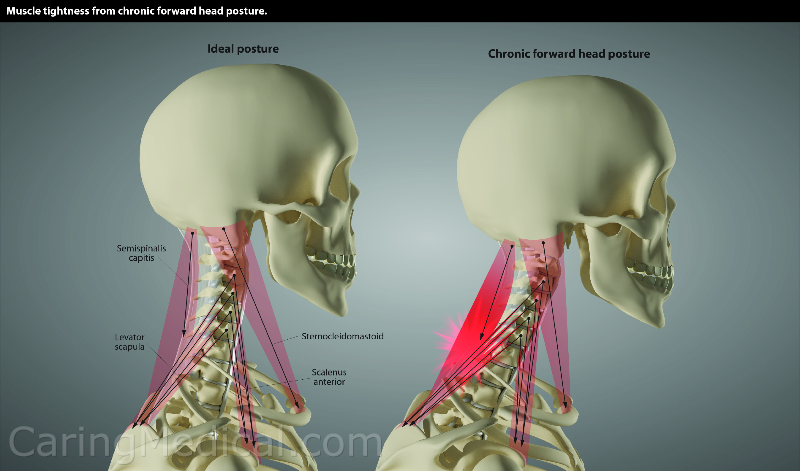

Problems with the vagus nerve can manifest in many domains: digestive issues, heart-rate irregularities, mood disorders, chronic inflammation, cognitive fog, and more. One often overlooked dimension is structural compression of the vagus nerve in the neck (cervical region).

Recent work (e.g., by Caring Medical & Hauser Neck Center) suggests that cervical spine instability or malalignment can lead to tension, stretch, or compression of the vagus nerve (and its associated ganglia), resulting in what they term “cervicovagopathy”.

Key symptoms flagged include: new-onset anxiety, tachycardia, nausea, bloating, digestive slow-down, deviated uvula, dizziness, lightheadedness.

For example, the neck vertebrae C1–C2 lie very near the carotid sheath (which houses the vagus) and upper cervical instability may strain or impinge the nerve fibers. Thus, structural issues in the neck can amplify vagus dysfunction, further interfering with gut-brain regulation, inflammation control, stress response and more. caringmedical.com

The gut houses trillions of microbes; their metabolites, signalling molecules and immune interactions feed back to the brain via the vagus. The brain uses the vagus to modulate gut motility, secretion, tone and barrier function (which in turn affects microbial populations).

Poor vagal signalling can lead to dysregulation: slower gut transit, increased gut permeability (“leaky gut”), aberrant microbiome‐brain signalling leading to psychological symptoms (anxiety, depression), cognitive fog, systemic inflammation. Conversely, practices known to enhance vagal tone (deep breathing, mindful movement, certain nutrition strategies) may support both gut and brain health.

Thus supporting the vagus nerve is one of the most integrative strategies you can adopt, not just for the gut or brain in isolation, but for your whole body system.

While nerve compression is often thought of in lower back or peripheral nerves, the upper cervical region (C0-C2) is a critical and under-recognised zone. According to research:

What this means for you: if you’re experiencing persistent digestive issues, mood/stress dysregulation, autonomic symptoms (e.g., heart-rate fluctuations, dizziness) and you have neck strain, forward-head posture or cervical trauma history, then considering the vagus-neck connection may open a new pathway of investigation and recovery.

Individuals with stress, digestive problems, autoimmune symptoms or neurodivergent profiles: supporting your vagus nerve means supporting your gut-brain axis, your immune regulation, your mood resilience and your cognitive clarity.

Teams and workplaces: high vagal tone in individual members correlates with better stress recovery, higher emotional regulation and greater productivity. When employees have nervous‐system balance, fewer absences and burnout risks are mitigated.

Children & students: The gut-brain connection is especially critical during development. Teaching movement, posture, breathing and gut-health awareness supports neurodivergent learners and those under academic stress.

Leaders: Looking to boost productivity, wellbeing and team resilience? Supporting the nervous system via vagal health (not just throughput metrics) creates a more sustainable culture of performance.

Through the gut-brain axis, this nerve plays a significant role in mood regulation, stress response, and cognitive function. Vagal tone plays a role in your mental health specifically around:

Stress and Anxiety: High vagal tone is associated with a greater ability to recover from stress, as it promotes the activation of the PNS. This helps reduce the physiological symptoms of stress, such as increased heart rate and muscle tension, and promotes a state of relaxation.

Conversely, low vagal tone is associated with heightened stress reactivity, a reduced ability to cope with stress, as well as with chronic stress. Enhancing vagal tone through practices such as deep breathing, meditation, and yoga can help improve stress resilience and reduce anxiety.

Depression: Low vagal tone has been linked to an increased risk of depression, as it is associated with reduced PNS activity and increased SNS dominance. This imbalance can contribute to the physiological symptoms of depression, such as fatigue, sleep disturbances, and gastrointestinal issues.

Cognitive Function: The vagus nerve’s influence on cognitive function is an emerging area of research related to cognitive processes like attention, memory, and executive function. High vagal tone has been linked to better cognitive performance, particularly in tasks that require self-regulation and decision-making.

If you’re ready to restore balance in your nervous system and support your overall well-being, explore my Psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) health coaching sessions and Qi Gong practices. Both approaches are designed to gently stimulate the vagus nerve, helping your body shift from stress to restoration. Through science-based guidance, mindful movement, and body awareness, you’ll learn to reconnect with your inner resilience and activate your natural healing capacity.

Maria Salazar- Founder

Bonaz, B., Bazin, T., & Pellissier, S. (2018). The vagus nerve at the interface of the microbiota–gut–brain axis. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12, 49. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins

.2018.00049

Breit, S., Kupferberg, A., Rogler, G., & Hasler, G. (2018). Vagus nerve as modulator of the brain–gut axis in psychiatric and inflammatory disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 44. https://doi.org/10.3389/

fpsyt.2018.00044

Tracey, K. J. (2002). The inflammatory reflex. Nature, 420(6917), 853–859. https://doi.org/10.1038

/nature01321

Bonaz, B., & Pellissier, S. (2022). Vagus nerve stimulation: A new promising therapeutic tool in inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Internal Medicine, 292(3), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13474

Groves, D. A., & Brown, V. J. (2005). Vagal nerve stimulation: A review of its applications and potential mechanisms that mediate its clinical effects. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 29(3), 493–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.neubiorev.2005.01.004

Kaniusas, E., Kampusch, S., Tittgemeyer, M., Panetsos, F., Gines, R. F., Papa, M., Kiss, A., Podesser, B., & Széles, J. C. (2019). Current directions in the auricular vagus nerve stimulation I – A physiological perspective. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 854. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00854

Hauser, R. A., Hauser, M., & Hauser, C. (2023). Vagus nerve compression and cervical spine instability: Understanding cervicovagopathy. Caring Medical Regenerative Medicine Clinics. Retrieved from https://www.caringmedical.com

/prolotherapy-news/vagus-nerve-compression-cervical-spine

Hauser, R. A. (2023). Ross Hauser, MD reviews cervical spine instability and its potential effects on brain physiology. Caring Medical. Retrieved from https://www.caringmedical.com

/prolotherapy-news/ross-hauser-md-reviews-cervical-spine-instability-potential-effects-brain-physiology

Wang, S. M., & Kain, Z. N. (2017). Vagal modulation of pain and inflammation: The case for Vagus nerve stimulation. Neural Regeneration Research, 12(3), 355–357. https://doi.org

/10.4103/1673-5374.202934

Sclocco, R., Garcia, R. G., Kettner, N. W., Isenburg, K., Fisher, H. P., Hubbard, C. S., & Napadow, V. (2019). The influence of respiration on brainstem and cardiovagal response to auricular vagus nerve stimulation: A multimodal study. Brain Stimulation, 12(4), 911–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.brs.2019.01.003

Farmer, A. D., Strzelczyk, A., Finisguerra, A., Gourine, A. V., Gharabaghi, A., Hasan, A., Burger, A. M., Jaramillo, A. M., Mertens, A., Majid, A., et al. (2021). International consensus on the vagus nerve and its stimulation: Report of a joint working group for the European Academy of Neurology and the European Federation of Autonomic Societies. European Journal of Neurology, 28(10), 3556–3583. https://doi.org/10.1111

/ene.15088

Breit, S., & Hasler, G. (2021). Vagus nerve stimulation and its effects on mood and cognition: A review of mechanisms and applications. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 17, 1783–1795. https://doi.org/

10.2147/NDT.S303347

Kaczmarzyk, M., et al. (2023). Cervical instability and the vagus nerve: Clinical observations and proposed pathomechanisms. Journal of Orthopaedic Research & Therapy, 12(2), 45–57.

Mayer, E. A., & Tillisch, K. (2011). The brain–gut axis in abdominal pain syndromes. Annual Review of Medicine, 62, 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1146

/annurev-med-012309-103957

Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2012). Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(10), 701–712. https://doi.org/10.1038

/nrn3346