Early childhood is the most sensitive period for brain development. During these years, the nervous system is shaped not only by genetics, but also by the quality of emotional care, safety, and environmental stability a child experiences. When children are exposed to chronic stress, emotional neglect, abuse, or unsafe environments, their developing brains adapt for survival rather than for learning, connection, and creativity. These adaptations may help the child cope in the short term, but they often come with long-term consequences for emotional regulation, cognitive flexibility, focus, memory, social confidence, and stress tolerance in adulthood.

Scientific research shows that early trauma alters the functioning of the stress system (HPA axis), the immune response, and key brain areas responsible for learning, emotional regulation, and executive function. Over time, this dysregulation increases vulnerability to anxiety, depression, burnout, attention difficulties, and reduced cognitive performance later in life. What begins as a survival response in childhood can become a limitation to performance and well-being in adulthood.

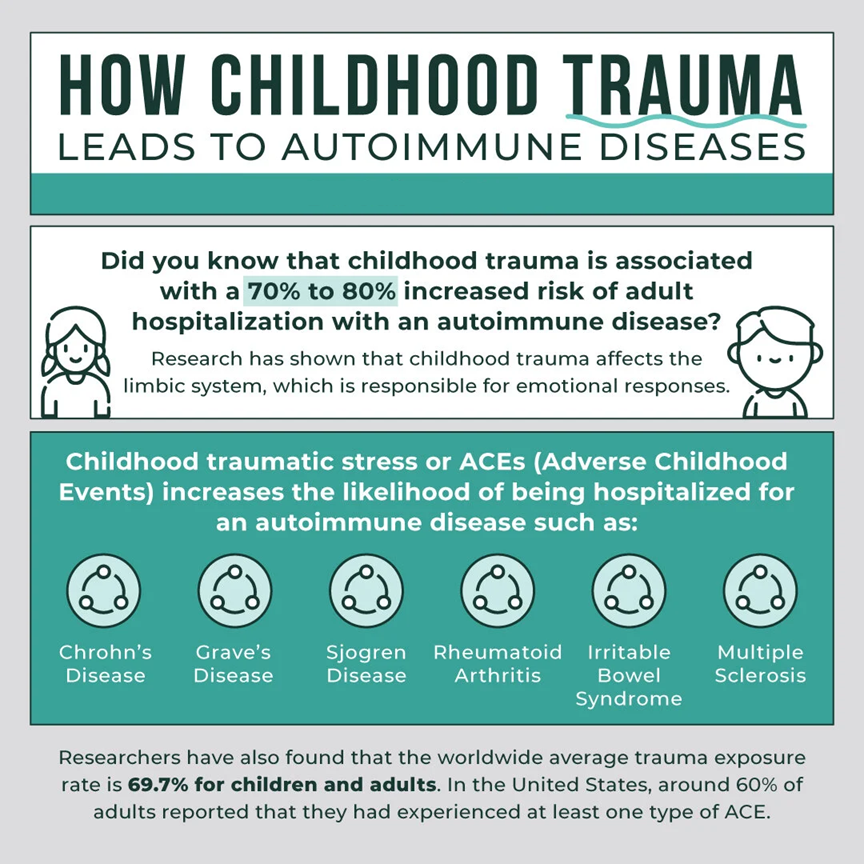

Children who grow up in chronically stressful or threatening environments also face significantly higher risks of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases later in life. Long-term activation of the stress system changes immune regulation, increasing systemic inflammation and impairing the body’s self-repair mechanisms. Studies show strong correlations between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and higher incidence of conditions such as autoimmune disorders, chronic pain syndromes, fatigue disorders, and inflammatory diseases. In simple terms: when a child’s nervous system is constantly in “survival mode,” the immune system is forced into long-term imbalance.

This connection is especially relevant for neurodivergent children, who already tend to experience heightened sensory sensitivity, emotional intensity, and stress reactivity. Without safe regulation support and understanding environments, these children are at even greater risk of long-term health and functioning challenges.

These children, whether with traits of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), dyslexia or other neurodivergent dispositions, often face challenges that begin long before diagnosis. Late diagnoses, misunderstandings, exclusion at school or among peers, and lack of support can create deep emotional, social, and health burdens. In many cases, families receive little guidance about neurodivergence and how to support their children’s unique needs early on, perpetuating isolation and unmet potential.

At the same time, growing scientific evidence suggests that neurodivergence is not a “disease” but a valid neurobiological variation. Many differences in brain wiring, sensory integration, information processing, and regulation are shaped by genetics, but are also strongly influenced by environmental factors: nutrition, stress levels, early-life experiences, and daily routines.

During childhood, the foundations of emotional, cognitive, and sensory self-regulation are shaped not only by genetics, but also by the quality of emotional care, safety, and environmental stability a child experiences. When children grow up in supportive, predictable, and emotionally attuned environments, they develop self-awareness, resilience, and adaptive coping skills that support learning, behavior, and social connection across life.

Supporting self-regulation from early childhood plays a crucial preventive role in mental and physical health. These skills not only improve attention, emotional balance, and learning outcomes, they also reduce long-term stress load and lower the risk of burnout, chronic fatigue, and inflammatory conditions later in life. Early interventions, mindful caregiving, sensory-aware environments, and emotional education can profoundly influence a child’s developmental trajectory, enabling them to thrive rather than struggle.

Children do not heal from stress through logic, they heal through repeated experiences of safety. Safe relationships, predictable routines, emotional validation, sensory-friendly environments, and body-based regulation practices allow the nervous system to return to balance. When safety is missing at home, at school, or in social environments, self-regulation cannot develop optimally, and the brain remains in a state of defense rather than growth.

However, when children are exposed to chronic stress, emotional neglect, abuse, or unsafe environments, their developing nervous systems adapt for survival rather than for growth, connection, and creativity. These early adaptations may help the child cope in the short term, but they often come with long-lasting consequences. Scientific research shows that early trauma alters the functioning of the stress system (HPA axis), the immune response, and key brain areas responsible for learning, executive function, and emotional regulation. Over time, this dysregulation increases vulnerability to anxiety, depression, attention difficulties, reduced cognitive flexibility, burnout, and diminished stress tolerance in adulthood. What begins as a protective survival response in childhood can later become a limitation to performance, health, and overall quality of life.

The impact of early trauma extends beyond mental and cognitive health into the immune system. Children who grow up in chronically stressful or threatening environments also face significantly higher risks of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases later in life. Long-term activation of the stress response disrupts immune regulation, increases systemic inflammation, and weakens the body’s ability to repair and restore balance. Studies consistently show strong links between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and higher incidence of autoimmune disorders, chronic pain syndromes, fatigue conditions, and other inflammation-driven illnesses. In simple terms, when a child’s nervous system remains in constant “survival mode,” the immune system is forced into long-term imbalance.

Recent studies highlight a strong link between nutrition, immune-brain interactions, and neurodevelopment:

Neurodivergent children often show insufficiencies in essential nutrients, including omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins (B-group, D), magnesium, zinc, and others, all of which play crucial roles in neurotransmission, mood regulation, cognitive function, and immune balance.

Dietary patterns and gut health appear particularly relevant: in children with ADHD or ASD, altered gut microbiota and inflammatory markers have been associated with behavioral symptoms, attention difficulties, and mood instability.

Given this, nutrition (combined with supportive lifestyle and environmental adjustments) becomes a powerful, non-stigmatising tool to support neurodivergent children’s well-being, reduce inflammation, improve concentration, and foster resilience.

Quadt, L., Csecs, J., Bond, R., et al. (2024). Childhood neurodivergent traits, inflammation and chronic disabling fatigue in adolescence: a longitudinal case–control study. BMJ Open. PubMed+2PMC+2

Hunter, K., et al. (2025). A closer look at the role of nutrition in children and adults with ADHD and neurodivergence. Frontiers in Nutrition. Frontiers+1

Shen, et al. (2025). Diet, inflammation and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with ASD. [Frontiers in Nutrition]. Frontiers

Kylie Wijeratne, Stephanie N. Pham, Delshad M. Shroff, Thomas H. Ollendick & Rosanna Breaux. (2025). Self-regulation in neurodivergent children and adolescents with and without co-occurring anxiety and depression. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. SpringerLink

Berni M, Scatigna S, Igliozzi R , Mazzotti S, Calderoni S, Martinelli, Tancredi R , Guzzetta A, Pecini C (2025). Early executive functions and self-regulation in preschool years as predictors for later neurodevelopmental disorders: a meta-analysis. Journal name. PubMed

Murray, A. L., Russell, A., & Calderon Alfaro, F. A. (2024). Early emotion regulation trajectories and childhood ADHD, internalizing and conduct problems. Development and Psychopathology. Cambridge University Press & Assessment

Muhammad Imran Arif a, Liang Ru a, Rena Maimaiti. (2025). Effect of different nutritional interventions in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reia.2025.202535