Psychoneuroimmunology: Where Mind, Body, and Immunity Meet

Psychoneuroimmunology or PNI explores one of the most fascinating truths about being human: our thoughts and emotions can shape our physical health. It’s the science that studies how the brain, the nervous system, and the immune system constantly communicate with one another. Instead of treating the body and mind as separate, PNI shows how deeply they work together to keep us balanced, healthy, and resilient.

I decided to study PNI after my aunt, who had also suffered from a chronic autoimmune illness, recommended it to me and even lent me the money to do so. During the course, I decided to take a microbiome test, which changed my life. After researching my own microbiome, I discovered an enzyme that is normally low in individuals with autism and ADHD: DAO (diamine oxidase), which is key to diagnosing histamine intolerance. I later asked a doctor to confirm this with a blood test.

The history of psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) is a fascinating journey spanning thousands of years and many cultures. It began with ancient mystics, philosophers and healers who considered the effect of mental states on physical health.

It has also been influenced by the historical shift from holistic to dualistic perspectives on the mind–body relationship, the latter of which gained significant traction in the early 17th century.

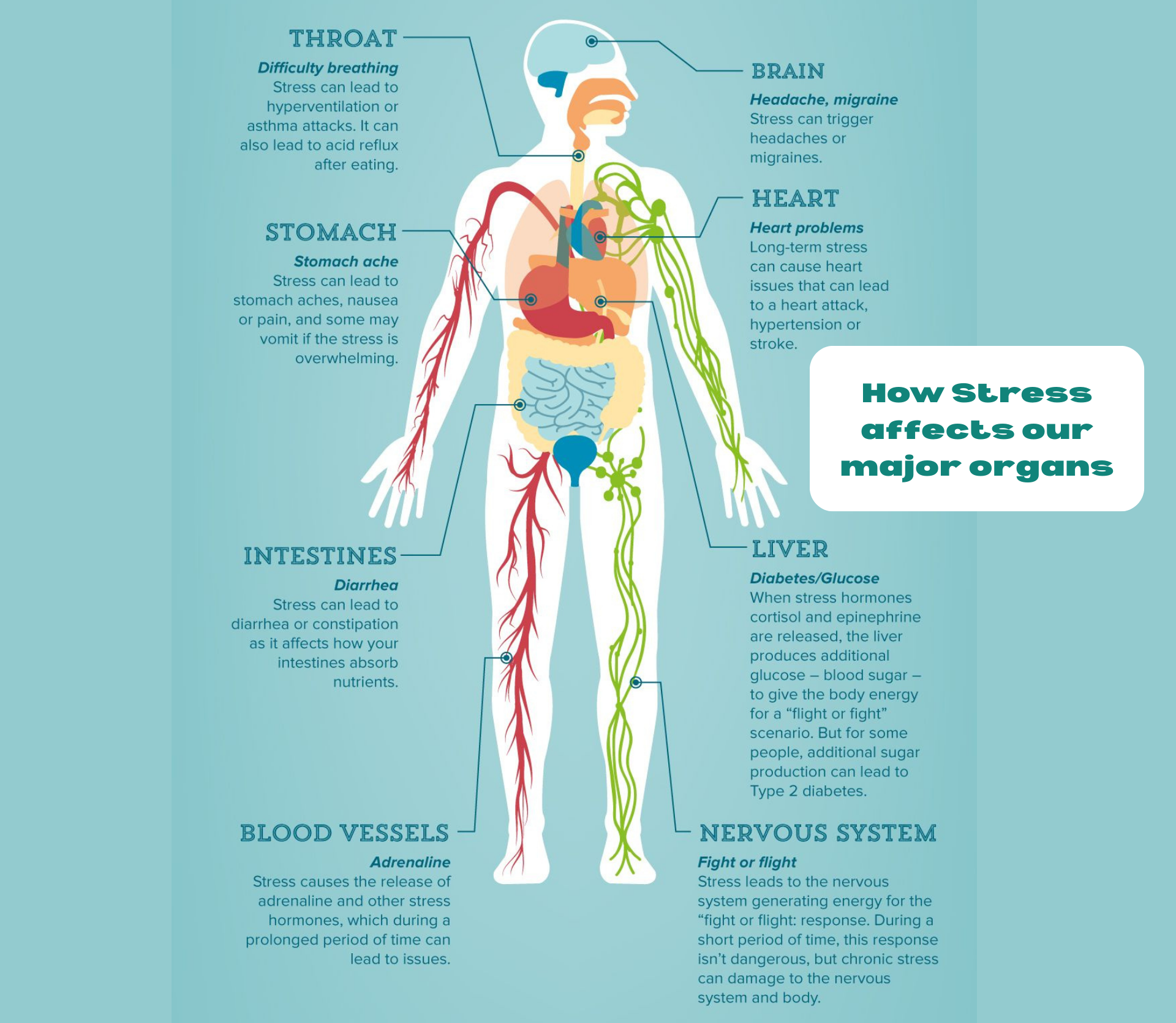

In the early 20th century, Harvard physiologist Walter Cannon was among the first to observe how emotions like fear or anger triggered visible physical reactions, the foundation of what we now call the fight or flight response. Later, Hans Selye expanded this understanding with his General Adaptation Syndrome, describing how ongoing stress exhausts the body’s systems and weakens immunity.

By the 1960s, researchers began noticing measurable immune changes in psychiatric patients. This led George Solomon to coin the term psychoimmunology, opening the door to a new way of studying the emotional roots of disease.

The real turning point came in the 1970s when psychologists Robert Ader and Nicholas Cohen made a groundbreaking discovery: the immune system could be conditioned, trained to respond to psychological cues. Their experiments showed that a simple sensory signal, like taste, could trigger immune suppression, proving that the brain and immune system were in constant dialogue.

Soon after, David Felten mapped nerve fibers directly connected to immune cells, and Candace Pert identified neuropeptides, chemical messengers that carry emotional information throughout the body. Together, their discoveries built the foundation of modern PNI and demonstrated that our emotions literally speak to our cells.

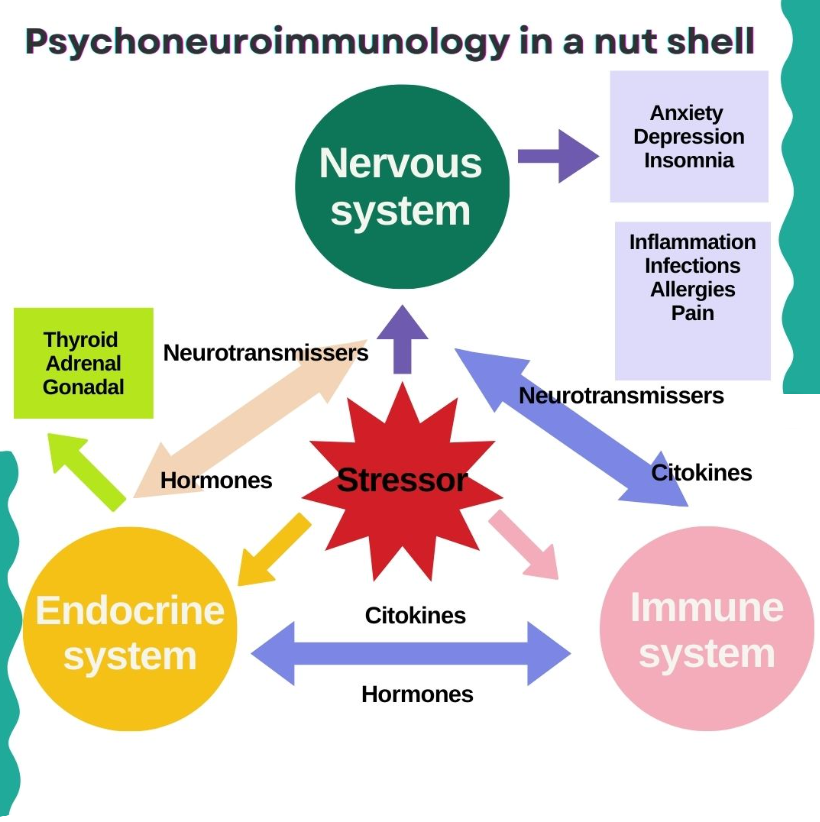

Today, PNI continues to uncover how this communication works. The main pathways, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system, regulate stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline. In healthy balance, these systems protect us. But when stress becomes chronic, they can disrupt the immune response, leading to inflammation, fatigue, and increased vulnerability to disease.

Molecules called cytokines also act as messengers between the brain and immune system. When overproduced, they can affect mood, sleep, and even trigger depressive symptoms, showing once again that mental and physical health are inseparable.

Among PNI’s most important findings is the deep link between chronic stress and illness. When the body stays in a constant state of alert, stress hormones suppress immune function, slow healing, and raise the risk of infections and inflammatory diseases. Over time, this imbalance can lead to burnout, autoimmune flare-ups, or mental health struggles. In contrast, relaxation, movement, and emotional connection help restore equilibrium, reinforcing both mental clarity and immune strength.

When stress is chronic, it can lead to anxiety, depression, and insomnia, disrupting your immune system.

This can cause inflammation, infections, allergies, and even chronic pain.

For example:

Other examples:

This explains why stress can make you sick, while meditation, exercise, and a healthy lifestyle can strengthen your immune defenses. Your thoughts and feelings matter more than you think!

Your mental and physical health are deeply connected. Managing stress, sleep, and emotions isn’t just about taking care of yourself, it’s about taking care of your immune system.

Psychoneuroimmunology bridges ancient wisdom and modern science. It gives language and evidence to what many holistic traditions have always known, that emotions, behavior, and biology are part of one living system. By caring for the mind, we support the body; by calming the body, we nurture the mind.

Our thoughts and emotions can directly affect your immune system and here’s how it works:

Your mind, nervous system, and immune system are in constant communication.

How?

At Corner of Movement, this understanding is at the heart of our approach. It’s why we integrate movement, mindfulness, and scientific education, helping individuals and organizations strengthen the connection between emotional well-being, immunity, and sustainable health.

If you’re ready to restore balance in your nervous system and support your overall well-being, explore our Psychoneuroimmunology (PNI) health coaching sessions and Qi Gong practices.

Both approaches are designed to gently stimulate the vagus nerve, helping your body shift from stress to restoration. Through science-based guidance, mindful movement, and body awareness, you’ll learn to reconnect with your inner resilience and activate your natural healing capacity.

Maria Salazar- Founder

Ader, R., & Cohen, N. (1975). Behaviorally conditioned immunosuppression. Psychosomatic Medicine, 37(4), 333–340. Landmark experiment demonstrating that psychological conditioning can directly alter immune responses.

Ader, R., Felten, D. L., & Cohen, N. (Eds.). (1981). Psychoneuroimmunology. Academic Press. Foundational book establishing the field; expanded in later editions (latest 4th edition, 2006).

Cannon, W. B. (1932). The Wisdom of the Body. W. W. Norton & Company. Introduced the concept of homeostasis and described the physiological effects of emotional states.

Felten, D. L., & Felten, S. Y. (1991). Innervation of lymphoid tissue. Psychoneuroimmunology, 2nd ed., Academic Press. Discovered direct nerve connections to immune cells, showing physical links between the nervous and immune systems.

Pert, C. B., Ruff, M. R., Weber, R. J., & Herkenham, M. (1985). Neuropeptides and their receptors: A psychosomatic network. Journal of Immunology, 135(2), 820s–826s. Revealed that neuropeptides act as communication molecules between emotions, the brain, and the immune system.

Selye, H. (1956). The Stress of Life. McGraw-Hill. Introduced the General Adaptation Syndrome and explained how chronic stress damages health.

Solomon, G. F., & Moos, R. H. (1964). Emotions, immunity, and disease: A speculative theoretical integration. Archives of General Psychiatry, 11(6), 657–674. One of the first papers linking emotions and immune function, preceding modern PNI.

Maier, S. F., & Watkins, L. R. (1998). Cytokines for psychologists: Implications of bidirectional immune-to-brain communication for understanding behavior, mood, and cognition. Psychological Review, 105(1), 83–107. Reviews the “immune–brain loop” and cytokine-mediated effects on mood and cognition.

Irwin, M. R., & Cole, S. W. (2011). Reciprocal regulation of the neural and innate immune systems. Nature Reviews Immunology, 11(9), 625–632. A modern summary of how stress and neural signals regulate immune activity and inflammation.